Everyone enters the sport of ultrarunning with preconceived notions (aka baggage) of what is and isn’t ultrarunning depending on how we were introduced to the community. My running journey started with roads/marathons where walking* was frowned upon. As I built my endurance and was able to run for longer and longer distances, walking became a sign of weakness or lack of fitness. When I started running ultras, I learned about the value of hiking the hills but at it’s core it was ultrarunning not ultrarunning.

* From this point forward I’m going to use the words walking and hiking interchangeably on purpose. People put far to many negative connotations on one word versus the other. Hiking isn’t “walking with a purpose”. Hiking is walking and walking is hiking. They’re both methods of moving your body forward while one foot is always in contact with the ground. Not that I’m different than everyone else as the Garmin activity for my daily walks/hikes is “Hiking” on my watch.

In hindsight, my baggage with walking is what contributed to my first DNF at C&O Canal. I reached a point where I was no longer able to run and I thought, “why bother?”. I wanted to run a hundred miles after all not just cover the distance. Like the accomplishment would somehow be tarnished if I didn’t run a certain percentage of the race. It was just a flat out ignorant opinion to have. Luckily, the seeds to my enlightenment were planted during that same race. Not too long before I was physically incapable of running, I was passed by a woman who was hiking faster than I was running. And by faster, I mean she practically blew by me like I was standing still. Thankfully, I was able to exchange a couple sentences with her whereby she explained that she did dedicated training each week to hike quickly. This stuck with me and I now incorporate 25-30 miles of dedicated walking each week in addition to the miles I run.

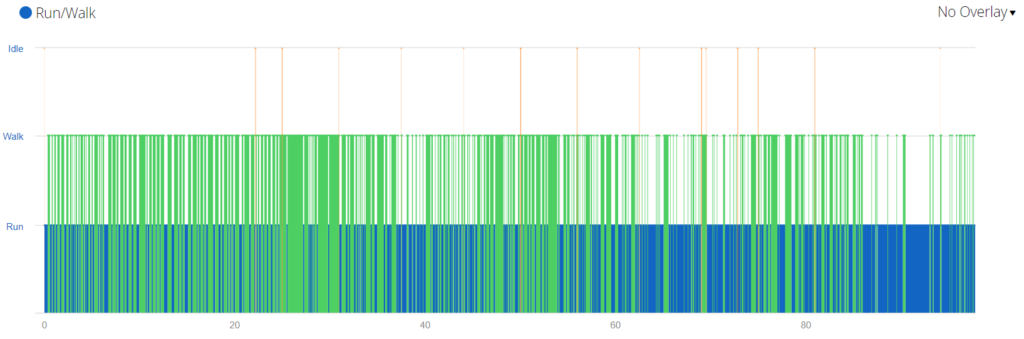

I’ve never looked at my run/walk mix in races before, but the below chart from Viaduct was pretty eye opening.

I knew I was walking quite a bit in the beginning of the race, but I had no idea it was that much. You can also see where I decided to walk more uphill on the second lap (miles 25-37.5) and run more heading downhill with a bit more walking after 40 as I had mostly banked the time I was looking for by that point. I remember running a lot at the end, but the amount of running from 60-75 miles is also a little surprising considering how poor I was feeling.

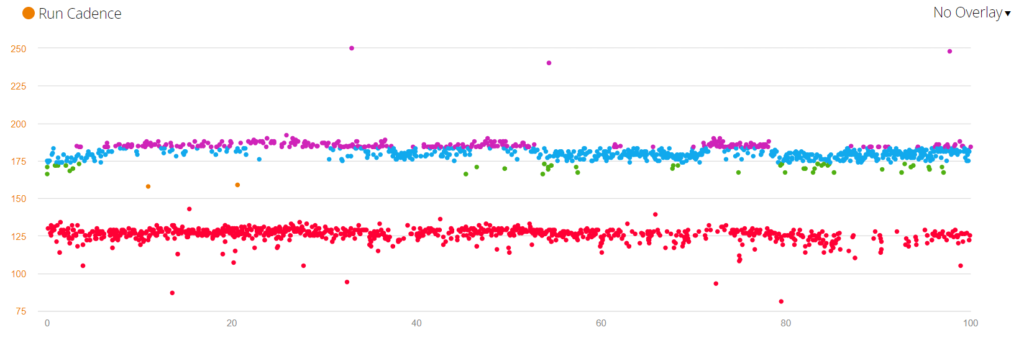

Now think about my lap times when looking at the above chart: 5:30, 5:30, 5:40, 5:44. I started running a lot more just to maintain pace and even then I was slowly slowing down. Interestingly, my run/walk cadence was pretty consistent throughout the race though did tail off a bit in the last 20 miles.

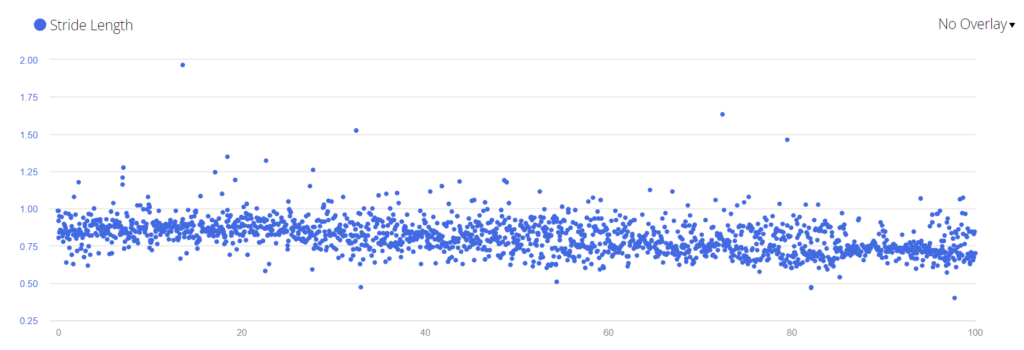

By process of elimination, my decreased pace must have been caused by stride length.

As your legs get tired, your stride length is just going to naturally shorten. There’s nothing you can do to prevent this entirely, however I believe the key minimizing this is walking early and often in ultras. And the faster you can walk, the more you can walk while maintaining the same pace (#math). The more you walk, the longer you’ll be able to run at your normal pace. Or even run at all. The key takeaway from my Viaduct race is that strong hiking early in the race enhances my late race endurance by letting me run more. And since running is faster than walking . . . stronger finishes!

Now let’s see if I can manage to remember this lesson the next time I pin a bib on.